For several years, we’ve been following and summarizing recent scientific findings on extremely high temperatures and their impact on our health. If you look at the key messages in these articles, the common thread is clear: extremes are already increasing and that trend will continue throughout this century. The impact on our health could be significant, but we can do something about it. The key messages in a selection of our posts.

More heat extremes in recent years

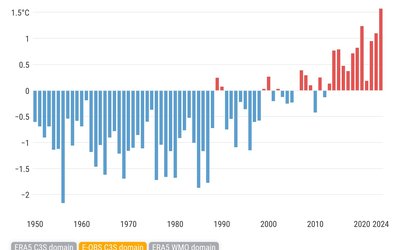

2024 was Europe’s warmest year since 1900. Ocean, sea and lake temperatures were the highest ever recorded. The number of heat stress days and tropical nights – with minimum temperature above 20°C – was the second highest on record, and is increasing. The number of ‘cold stress days’ was the lowest on record.

Heatwaves in northern Europe are increasingly similar to those in the south. The increase of heatwave frequency and heatwave intensity in the period 1998–2021 was much larger in northern European countries than in France and the Iberian Peninsula.

50% of European territory is now experiencing unusually warm temperatures in the summer in comparison to the situation half a century ago.

More heat extremes in the future

Summer length in the Northern Hemisphere is increasing. Between now and 2100, each summer will last about half a day longer than the previous one, on average.

By the end of this century, far more records will be set under a high-end than under a low-end scenario of climate change, and far more of these records will be ‘smashing’.

More heat-related deaths in recent years

In recent decades, heat has been the leading cause of reported deaths due to extreme weather and climate events in Europe. Heat-related deaths in Europe have been estimated to be around 47,700 and 61,700 in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

Twenty years after the deadly heat of 2003, Europe’s heat response is still ineffective.

More heat-related deaths in the future

In Europe, on average, there are now roughly ten cold-related deaths for each heat-related death. However, the increase of heat-related mortality as temperature rises follows a steeper curve than the decrease of cold-related mortality. The increase in heat-related deaths will outpace the decline in cold-related deaths in Europe in the second half of this century.

70 years from now, nearly half of the global urban population could be exposed to high heat stress.

The fingerprint of climate change

Extreme European heatwaves are now several times more likely due to climate change.

Of all extreme weather events in recent years, 74% were made more likely or severe because of climate change. Most of them are related to heat.

What we can do

We can cool our cities much more than we currently do. For 100 cities spread across Europe – from southern Scandinavia to the south of Spain and from Ireland to the Baltic States and Greece – the potential to reduce the urban heat island effect has been calculated. The average urban heat island effect for all 100 cities is 1.43°C. The current cooling - by trees f.i. – is 0.45°C on average. There is still a large potential for extra cooling from more greening and less pavement, ranging between 0 and 1°C, with an average value for all 100 cities of 0.49°C.

Trees can cool European cities up to 12 °C on a hot day.

Trees have reduced heat-related mortality in recent years in London by around 16%. London’s strategy to increase tree coverage by 10% would reduce this mortality by a further 10%.