By Wilfried ten Brinke

This longread is based on a large number of scientific sources assembled by the ClimateChangePost. Check out the forest fire pages on www.climatechangepost.com for more details.

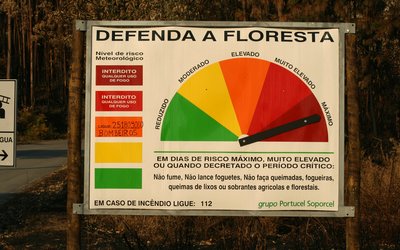

August 2016. Large wildfires, out of control according to the media, rage across California. Again! On the Portuguese island of Madeira the capital Funchal is covered in black smoke of wildfires approaching from all sides. Again! The impacts of climate change on natural hazards cast their shadows in the increasing numbers of wildfires. The causal connection is hard to deny.

Southern European countries: hundreds to thousands of wildfires, in just one summer!

Almost every year from June to September large wildfires burn at several spots across southern Europe, including the Canary Islands and Madeira. Wildfires are especially concentrated in July and August. The annual number of fires strongly varies from hundreds in one country to thousands in another. In Spain, for instance, over the last 30 years some 400,000 wildfires have occurred. During 1991-2002 each year 0.55% of the total forest area of Spain burnt. Similar numbers have been reported for Italy: every year an average of 11,000 fires occur, destroying more than 50,000 ha of wood each year. In the past 20 years 1,100,000 ha of forest have been burnt in Italy.

Not all summers are equally devastating of course. After all, not all summers are equally hot and dry, and a devastating summer in one part of Europe may not be that devastating in another. The summer of 2000 led to many wildfires in Croatia: 590 fires burnt 66,785 ha of forest and forest land; during the ten preceding years on average 330 fires burnt 19,164 ha of forests and woodland area in Croatia annually. For Montenegro the number of wildfires peaked in 2000 and 2003. In Albania 352 major fires burnt throughout Albanian parks and forests during 2006 - 2007, burning entire ecosystems and pastures, sometimes leaving behind areas with not a single tree left for tens of kilometres.

One of the worst wildfire seasons in Europe so far was the summer of 2003. More than 25,000 fires were recorded in Portugal, Spain, Italy, France, Austria, Finland, Denmark and Ireland. The estimation of forest areas in EU member states destroyed reached 647,069 hectares. The country worst hit was Portugal. Spain came second. This was by far the worst wildfire season Portugal had faced in the last three decades. Nearly 50% of all EU wildfires this summer burnt in Portugal and the northwestern provinces of Spain. These fires were directly responsible for the loss of 21 lives. 425,000 ha of forest burnt in Portugal alone, corresponding to approximately 13% of the total forest area in the country. By way of comparison: in the period 1980 - 2004, fires have burnt over around 2.7 million hectares of Portuguese forestland.

Increasing trend since the 1970s

In southern Europe, fire frequency and wildfire extent significantly increased after the 1970s compared with previous decades due to fuel accumulation and extreme weather events, especially in the Mediterranean countries. In these countries, both fire frequency and total area burnt increased, but the increase in fire frequency was more sustained than the increase in total area burnt. Most wildfires are caused by people.

Dead wood and droughts fuel wildfires

More fires not necessarily mean that a larger area is burnt. The number of ignitions appears to have very little effect on the total area burnt. In fact, the total area burnt doesn’t seem to get less no matter how hard countries try and succeed to reduce the number of ignitions and extinguish fires. This is probably due to the fact that total annual area burnt largely depends on the characteristics of the vegetation: the amount of accumulated biomass and drought conditions in combination determine the amount of fuel for wildfires.

Processes that allow the natural accumulation of fuel, like reducing the number of ignitions or increasing the fire fighting capacity, permit the creation of continuous areas with a high fuel load, which will burn under adverse meteorological conditions and produce large fires. On the contrary, processes that eliminate patches of fuel, like a high number of ignitions, non-fire suppression, or prescribed burning, create a patchy mosaic in the vegetation that can behave as fuel-breaks under some circumstances, and reduce the extension of some fires that, otherwise, would become large fires.

The inter-annual variability in area burnt in Spain in the last three decades of the previous century was significantly related to the summer rainfall: in wet summers the area burnt was lower than in dry summers. Furthermore, summer rainfall was significantly cross-correlated with summer area burnt for a time lag of 2 years, suggesting that high rainfall may increase fuel loads that burn 2 years later.

Fuel availability and vegetation density was also an important cause of the large burnt areas of the 2007 fires season in Greece. Over the last 150 years, 2 out of 4 years with greatest increase in burnt area occurred in 1998 and 2007 when both above-average temperatures and below-average precipitation coincided during the mid to late fire season. These fires most likely have had more surface burning fuel to propagate compared with those in previous decades because of rural depopulation in northern mountains of the Mediterranean, thus resulting in reduced harvesting of biomass and longer periods of fire exclusion (during which burning fuel accumulated) because of lower human activity.

It’s the combination of accumulated biomass and drought conditions that determine the number and size of wildfires. During the period 1961 - 1997 there was a statistically significant increasing trend and a positive correlation between the number of fires and area burnt and the annual drought episodes in Greece. The average number of fires and area burnt were significantly higher in Greece during the sub-period 1978 - 1997, when Greece entered a prolonged period of drought, compared to the previous sub-period 1961 - 1977. From a statistical analysis of fire occurrence in Greece during 1900 - 2010 it was concluded that total area burnt at the national scale is controlled by precipitation totals rather than air temperature.

Increasing trend since the 1970s: more fuel, more droughts

The role of climate and human-driven fuel changes on the fire regime change over the last 130 years in the Valencia province of Spain has been evaluated based on contemporary statistics plus old forest administration dossiers, newspapers, rural population and climatic data. The result suggest that there was a major fire regime shift around the early 1970s in such a way that fires increased in annual frequency (doubled) and area burnt (by about an order of magnitude). It was concluded that the main driver of this shift was the increase in fuel amount and continuity due to rural depopulation (vegetation and fuel build-up after farm abandonment) suggesting that fires were fuel-limited during the pre-1970s period. Climatic conditions were poorly related to pre-1970s fires and strongly related to post-1970s fires, suggesting that fires are currently less fuel limited and more drought-driven than before the 1970s.

Out of control

At times, the number of fires exceeds coping capacity of countries’ fire fighters. In the summer of 2007, heat waves hit southern and central Europe. Dry conditions helped trigger fire breakouts throughout the region, and several people were reported dead directly from the fire. In Bulgaria, fire fighters were not prepared for the approximately 1,800 fire breakouts during the 2007 heat wave. The country was forced to declare a state of emergency and seek foreign aid. In Croatia, 12 fire fighters were encircled by flames and died. Over the past 30 years, wildfires in Aragón (northeastern Spain) have became more extreme, with fire behaviour more and more often exceeding fire fighting capabilities, and fire agencies experience difficulties in suppressing extreme-behaviour fires while providing safety for both fire fighters and citizens. If high temperature days become more frequent and conditions are able to decrease air humidity and fuel moisture and increase the fire behaviour potential, areas such as Aragón may be facing larger wildfires in the future, and very likely extreme-behaviour fires beyond suppression capacity.

The summer of 2007 was also characterized by uncontrolled wildfires in Greece. This summer, the country was hit by three consecutive heat waves (46°C) that, along with the strong winds and the low relative humidity (9%), resulted in forest fires breaking out. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), Greece has experienced more wildfire activity during the summer of 2007 than other European countries have over the last decade. In total, over 8,933 fires have been recorded in the country following the third heat wave the country had experienced in that period. The mountainous southern peninsula of Peloponnesus was the worst affected region: 1,477 fires broke out in the Peloponnese region, burning 10,196 km2 of land, 6,633 km2 of which were protected forests and natural areas. The estimation for the cost of the damages for the 500,000 people affected was close to 3 billion euros according to European sources, while other moderate estimations have found it to be close to 2.2 billion US dollars. During the 2007 summer period, 68 people were killed, while another 2,094 people were injured. More than 100 villages and settlements were damaged; the burnt forest and agricultural land constitutes about 2% (190,836 ha) of the total area of Greece. Extended wildfires also burnt large areas of Macedonia.

Increasing threat for southern Europe

Large wildfires increasingly become a major threat for southern Europe. In a study on wildfires in northeastern Spain, so-called ‘main wildland fires’ are defined as those over 60 ha. These large fires, 2.5 % of the total number of fires in this area, accounted for 85 % of the total area burnt in northeastern Spain in the 1978 - 2011 period. High temperature days more and more determine the origin of large wildland fires in this region. The annual number of days with these high temperatures increases. The authors of this study warn that in the future we might be expecting larger fires and could face extreme-behavior wildland fires beyond firefighting capacity. Wildland fires are mostly happening from June to September. Fire season seems to be starting earlier and last longer than in former years.

Climate change may already have affected wildfire season in southern Europe. The number and intensity of fires may have increased due to higher summer temperatures and prolonged droughts. According to research on wildfires in Spain fire season seems to be starting earlier and last longer than in former years: the number of high temperature days in June is already increasing.

Future projections: Southern Europe’s wildfires risk continues to increase

All model studies indicate that wildfire risk will increase in southern Europe. The number of days with a high risk of fires starting will increase and so will the length of the fire season. In fact, in the second half of this century the southern Mediterranean may be at risk of wildfires all year round.

The increase of wildfire risk will probably affect nearly the entire Mediterranean region, especially inland locations, but also the southern part of the European territory of Russia. Only in the southeastern Mediterranean (the islands of Crete, Sardinia, Sicily, Peloponnese, Cyprus) fire risk may not change that much. In the Iberian Peninsula, northern Italy and over the Balkans, the period of extreme fire risk lengthens substantially. Projections of forest fire risk in 2030 - 2060 compared with 1961 - 1990 suggest that there will be 2 to 6 additional weeks of fire risk everywhere, except for the south of Italy and Cyprus. The maximum increase is again inland (Spain, Balkans, north of Italy, Central Turkey), where at least an additional month with risk of fire is expected. The south of France, Crete, and the coastal area of the rest of the Mediterranean Region also show a significant increase in the number of days with fire risk (1-4 weeks), but not in the number of extreme fire risk.

The annual burnt area in Southern Europe is projected to increase accordingly. By how much is hard to say. By a factor of 2 to 3 in 2075 compared with the present situation, some model projections indicate. It may even be a factor of 3 to 5 by 2100, according to others. Much lower increases have also been reported. For Portugal, for instance, an increase of mean burnt area in July and August by ‘only’ 11% for the period 2071 - 2100 has been projected compared with the period 1980 - 2011. Of course, these model projections vary because different models have been used, different scenarios of climate change have been assumed, different future time slices and reference periods have been chosen, and a number of other assumptions have been made.

Scientists agree

Scientists seem to agree that fire risk will increase in southern Europe, the fire season will last longer, and more fires will start. It makes sense that the annual burnt area increases accordingly. By how much remains to be seen and depends on processes that call for further research. One important aspect is the availability of fine fuel (low cover): hotter summers may limit the availability of fine fuel and favour fuel gaps, thus reducing the spread of large fires. Less rainfall may lead to less grass fuel being available to support fires. On the other hand, dry weather may damage ecosystems, and dead biomass may accumulate as a result, thus increase the risk of large wildfires. In addition, forest fires are expected to encourage the spread of invasive species that in turn, have been shown to fuel more frequent and more intense forest fires. Currently fuel-humidity limited regions could suffer a drastic shift of fire regime with an up to 8 fold increase of annual burnt area between now and 2100, due to a combination of fuel accumulation and severe fire weather, which would result in a period of unusually large fires. In areas that are already dry today, the impact of climate change on fire regime is probably less.

Clearly, land-use and land-cover changes are important factors to consider when preparing for changes in wildfire risk. Mediterranean mountainous areas may face a very large threat from wildfires in the twenty-first century, if socioeconomic changes leading to land abandonment and thus burning fuel accumulation are combined with the drought intensification projected for the region under global warming.

Follow-up on this longread

How is wildfire risk changing in the rest of Europe? What measures are needed to fight wildfires that seem to get out of control every now and then? What strategies can be used to limit the increasing wildfire risk? These questions will be answered in the coming weeks in follow-up articles on the ClimateChangePost.

Source: www.climatechangepost.com

Photo: ProjectLM (www.flickr.com)